Would you rather live in 2023 or a hundred years ago in 1923?

Does life in the famous Roaring Twenties before “all this technology ruined our lives and our planet” sound romantic, pure, and simple?

Maybe a glance at what life was really like in 1923 might provide us a better understanding of how grateful we should be that we’re alive in 2023.

Let’s dive in…

A Snapshot of The Roaring Twenties

The year is 1923, and the United States is under the spell of the Roaring Twenties.

While it's easy to romanticize this era, picturing Jazz Age flappers, speakeasies, and economic prosperity, the reality of everyday life for the average American was not as glamorous.

For many, it was a time of hardship, struggle, and adjustment in the wake of World War I and amidst the rapid pace of industrialization and urbanization.

Each day would begin early, often with the crowing of roosters, even in urban areas. For the vast majority of households, there was no central heating. Coal was the primary fuel for home heating, and the task of starting the day's fire fell to the man of the house. This would involve shoveling coal into a stove or furnace, a dirty job that filled the air with soot and grime.

Breakfast was a hearty affair, with foods like eggs, bacon, porridge, and bread commonly consumed. Many products we take for granted today—pasteurized milk, bottles of orange juice, prepackaged cereals, or convenient to-go coffee—were nowhere to be found.

Cooking was a time-consuming task, typically handled by the woman of the household, who was also responsible for other domestic chores such as cleaning, laundry, and child-rearing.

The rapid pace of urbanization brought its own set of challenges. Overcrowding, poor sanitation, and inadequate housing were commonplace in cities, exacerbating public health issues. Prohibition was in full swing, leading to an increase in organized crime and illegal speakeasies.

Hardships of 1923 were not just physical but also social. Women had only just recently gained the right to vote, and their struggle for equal rights was far from over. Racial tensions were high, with the Ku Klux Klan experiencing a resurgence and segregation still the law in many places.

Moreover, the cost of living in 1923 reflects the hardships that many ordinary Americans faced. A dollar in 1923 is equivalent to about $16.50 today, with workers median income ranging from 9 cents to 17 cents per hour, equivalent to $1.48 to $2.80 today.

Before the widespread adoption of sanitation and other technologies such as pasteurization (which was only made mandatory by the FDA in 1987), the average life expectancy was about 56 years for men and 58 years for women, reflecting the significant health and social challenges of the time.

One of the clearest ways to see the challenges of the period is through the lens of work.

As much as many of us complain about working 50 or 60 hours per week today, imagine 80-hour work weeks as well as the need to send your kids off to the factory to make ends meet.

Work Life in 1923 and the Persistence of Child Labor

In 1923, the U.S. was a predominantly agricultural and industrial nation. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the manufacturing industry employed around 8.3 million people in 1920, and the numbers grew steadily throughout the decade.

This represented a continuation of the trend towards industrial employment, which had been stimulated by the demands of World War I and was sustained by the economic prosperity of the 1920s.

Unemployment was relatively low in 1923, with the annual average rate hovering around 3.2% according to the U.S. Department of Labor. This was a marked improvement over the post-war years when demobilization caused a brief spike in unemployment. The low unemployment rate in 1923 can be attributed to the economic prosperity of the time, characterized by rising wages and increased consumer spending.

But don’t let those high-level positive figures fool you.

Work life for the average American in the early 1920s was significantly more strenuous and less regulated than it is today. The 40-hour workweek would only become standardized in the U.S. with the passage of the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1938, and many labored for ten to twelve hours a day, six days a week to survive. Industrial workers faced hazardous conditions in factories, with little safety regulation and no health insurance.

Perhaps the clearest indication of the hardships of work life during this period is the continued use of child labor.

In the early 1920s, more than two million children under the age of 15 were working. These children were often forced to work long hours under dangerous conditions. Many were also denied the opportunity to go to school, which led to high rates of illiteracy among child laborers.

According to a 1920 census report in the U.S., approximately 1 in 10 children between the ages of 10 and 15 were engaged in gainful employment. The numbers were even higher in some southern states, where child labor was more commonly used in agriculture and industry. Children as young as 5 or 6 years old were found to be working in factories, mines, and farms, but it was more common for children to start working at the ages of 10 or 12.

It was not until 1938 that the first robust child-labor law was enacted.

In 1908, photographer Lewis Hine was employed by the newly-founded National Child Labor Committee (NCLC) to document child laborers and their workplaces nationwide. Hines traveled the country and created portraits of young newsboys, miners, mill workers, and others.

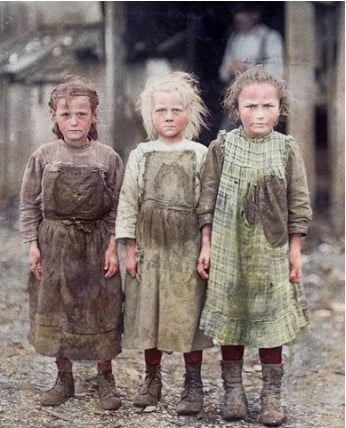

Here are a few examples, taken from a 2015 profile of Hines’ work in The Atlantic:

The above picture shows Josie (6 years old), Bertha (6 years old) and Sophie (10 years old), who worked regularly at the Maggioni Canning Company. Work began at 4am and the three would make from $9 to $15 a week. Sophie would do six pots of oysters a day and her mother who also worked with her said, "She don't go to school. Works all the time."

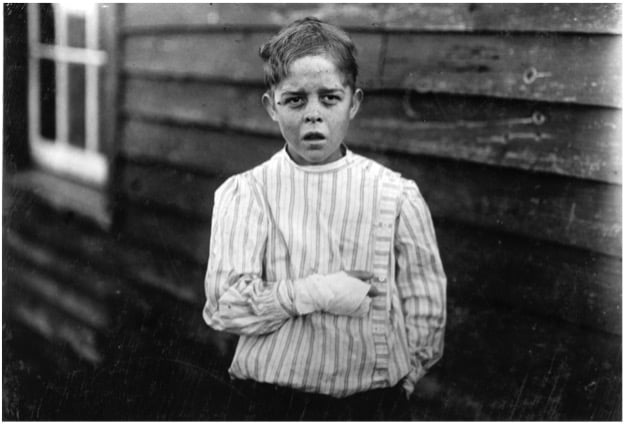

A photograph taken on October 23, 1912, captures the image of a young, injured mill laborer, Giles Edmund Newsom. He suffered his injuries on August 21, 1912, while working at Sanders Spinning Mill, located in Bessemer City, North Carolina.

An unfortunate accident happened when a piece of equipment toppled onto his foot, smashing his toe.

This incident made him lose balance, causing him to tumble onto a spinning machine where his hand was caught in unprotected gears, which resulted in the crushing and subsequent loss of two of his fingers.

During a legal investigation, Giles revealed that he was merely 11 years old at the time of the accident. He and his younger brother worked in the mill several months before the accident. Their mother tried to blame the boys for getting jobs on their own, but she let them work several months.

Why This Matters

Drawing a clear picture of life in 1923 is not a mere exercise in nostalgia—it’s a mirror reflecting how far society has come in just a century.

The world of the Roaring Twenties was not merely glitz and glamour but was marred by struggles that seem foreign to us today. By understanding the genuine daily challenges, limited conveniences, and social disparities of that time, we can find deep gratitude in the modern comforts and rights we now enjoy.

Recognizing the rapid progress made in just 100 years offers hope for future possibilities.

A we march toward the Singularity, it’s important to realize that the speed of change is accelerating.

Every aspect of how we live our lives will change in the next decade—from how we raise our kids to how we run our companies. In the next 10 years, those surfing on the tsunami of change (rather than getting crushed by it) will create more wealth than was created in the past century.

The driving force of all this change is—and has always been—technology: turning what was once scarce into abundance, over and over again.

In our next blog, we’ll look more closely at how slow the pace of innovation and technological development was 100 years ago, to help us better appreciate just how far we’ve come, and where we are going.

Life 500 Years Ago... Sucked

Key Tech Innovations of 1923